Art in Working Life

The Sculpture of

Phill Rooke

Walter Benjamin in his famous essay The Author as Producer stated that the socialist artist, rather than just saying the right thing or exhibiting the right tendency, must change the means and mode of art production. It is, from this point of view, useless to produce ‘revolutionary’ works for the middle-class gallery or the middle-class bookcase. Instead, the mode of production must be collectivised and situated within the workers’ economy and social life. This is often not well understood in left circles.

It is worthwhile then to celebrate the work of Auckland-based artist, Phill Rooke, who worked for an initial period as an art in working life artist in the UK and then in Australia, when there were, unbelievably, for a period, arts officers attached to trade unions. Phill worked in factories, studying the movements of the workers and then, in dialogue with them created sculptures, before funding for that field dried up with the arrival of the new right.

Arriving in New Zealand in the 1990s, Phill then turned to working within geographic communities, creating works that often told the history of that community, with an emphasis on the contribution made by the working class. These works would then be permanently displayed in a communal space e.g. the Grey Lynn Community Centre.

Unfortunately, funding for the community art field was also marginalized when the NZ Arts Council was restructured in 1994. From there it has all been creative industries with an emphasis on tourism, corporate partnerships, and the art sector as a PR arm of the government.

Phill now creates icons for the individual buyer.

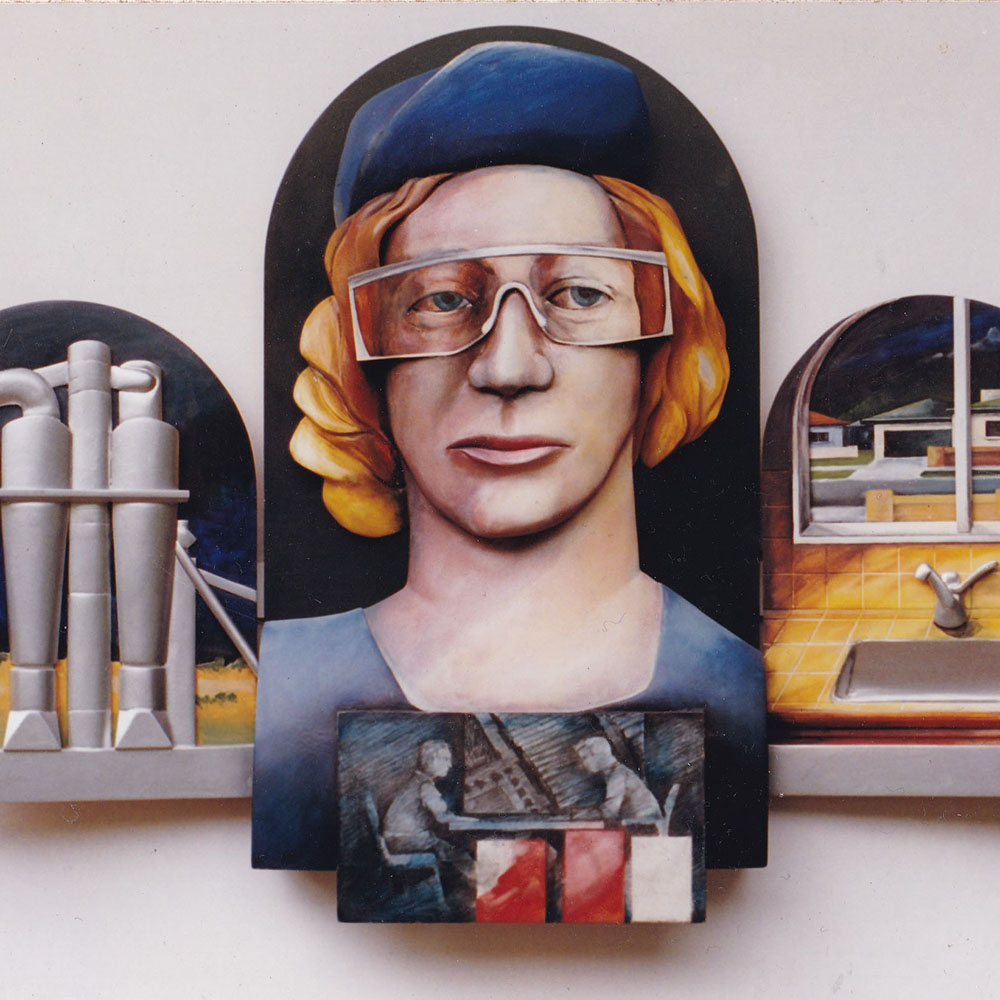

But his work continues to celebrate the physical process of the working person, that ability, past and present, to create and to alter, the physical world in which we live. Of course, the natural environment is the wider context in which this human physical activity takes place. As part of this paradigm, there is the physical creation of the work of art; the sculpture or painting or drawing being the work of the artist as worker.

This celebration of process has a strong spiritual quality, wonder, and awe, in the same way that the painting or sculpting of the nativity, as a celebration of God becoming part of the physical world, is filled with wonder and awe.

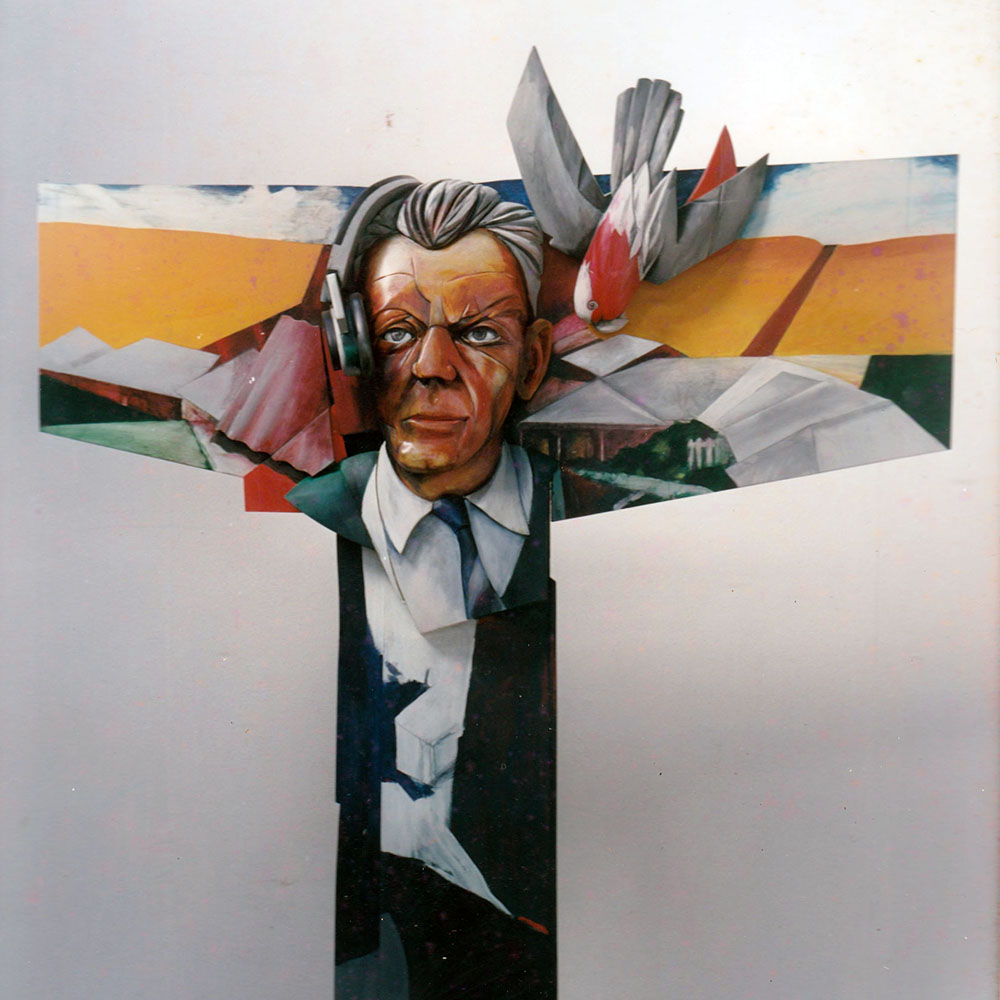

Rooke’s later sculptures accordingly have the physical shape and presence of the icon.

But, of course, while the working person creates and alters the physical world, under capitalism, the fruits of his or her labours are owned by the capitalist, and this is the source of the revolutionary impulse. In the same way that Christ was rejected and his physical presence murdered, this being the subject of religious art, the worker is alienated from his or her work. There is a resonance here for Rooke; a tension and knowledge that underlies his work, with the natural world often echoing this tension – birds as well as symbolising liberty have the paranoia necessary for survival.

The paradigm behind Rooke’s work inevitably involves a critique of the mainstream art world, which celebrates subjective, individualist ‘works of genius’, which then become a commodity for the investor. Art is privatized, with criticism a reading for the market, and the creation of importance being a part of marketing. This extended into the Cold War, with abstract expressionism, as a movement, being funded by the CIA in an ideological battle against the social realism of the USSR. This has morphed into post-modernism as the culture of neoliberalism or late capitalism. Diversity leads to the need for niche-marketed commodities, both in the shopping mall and the gallery.

Portrait of Nurse Shadbolt, a NZ nurse in the Spanish Civil War

In this global cultural narrative, it is easy for Rooke’s work to be marginalized (Marxist, religious, and community-oriented), a nostalgia, in the same way as the worker or the working class are seen as nostalgic concepts. Yet that is simply untrue. Anyone who works with or closely observes a builder, plumber, sawmill worker, digger-driver, or gardener at work will see the pride that remains, the pride of making or healing a house or making a road or cycleway or landscape, the pride in making the world a better place. But the tensions remain of who ultimately owns the results of the work.

Accordingly, those basic physical processes that Rooke celebrates, in his icons, are a necessary reminder of what is at stake, both materially, socially, and spiritually.

Paul Maunder. Mahi Tupuna – Blackball Museum of Working Class History.